|

|

Sleeve Notes

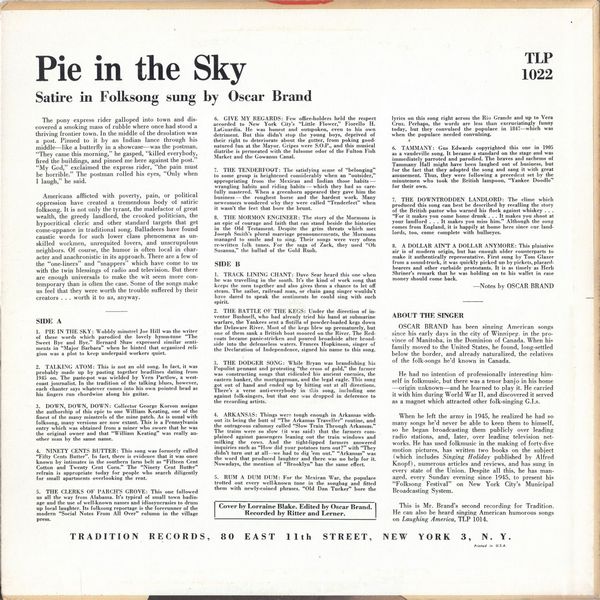

The pony express rider galloped into town and discovered a smoking mass of rubble where once had stood a thriving frontier town. In the middle of the desolation was a post. Pinned to it by an Indian lance through his middle — like a butterfly in a showcase — was the postman. "They came this morning," he gasped, "killed everybody, fired the buildings, and pinned me here against the post." "My God," exclaimed the express rider, "the pain must be horrible." The postman rolled his eyes, "Only when I laugh," he said.

Americans afflicted with poverty, pain, or political oppression have created a tremendous body of satiric folksong. It is not only the tyrant, the malefactor of great wealth, the greedy landlord, the crooked politician, the hypocritical cleric and other standard targets that get come-uppance in traditional song. Balladeers have found caustic words for such lower class phenomena as unskilled workmen, unrequited lovers, and unscrupulous neighbors. Of course, the humor is often local in character and anachronistic in its approach. There are a few of the "one-liners" and "snappers" which have come to us with the twin blessings of radio and television. But there are enough universals to make the wit seem more contemporary than is often the case. Some of the songs make us feel that they were worth the trouble suffered by their creators … worth it to us, anyway.

PIE IN THE SKY: Wobbly minstrel Joe Hill was the writer of these words which parodied the lovely hymn-tune "The Sweet Bye and Bye." Bernard Shaw expressed similar sentiments in "Major Barbara" when he hinted that organized religion was a plot to keep underpaid workers quiet.

TALKING ATOM: This is not an old song. In fact, it was probably made up by pasting together headlines dating from 1945 on. The paste-pot was wielded by Vern Partlow, a west-coast journalist. In the tradition of the talking blues, however, each chanter says whatever comes into his own pointed head as his fingers run chordwise along his guitar.

DOWN, DOWN, DOWN: Collector George Korson assigns the authorship of this epic to one William Keating, one of the finest of the many minstrels of the mine patch. As is usual with folksong, many versions are now extant. This is a Pennsylvania entry which was obtained from a miner who swore that he was the original owner and that "William Keating" was really an other man by the same name.

NINETY CENTS BUTTER: This song was formerly called "Fifty Cents Butter". In fact, there is evidence that it was once known by intimates in the southern farm belt as "Fifteen Cent Cotton and Twenty Cent Corn." The "Ninety Cent Butter" refrain is appropriate today for people who search diligently for small apartments overlooking the rent.

THE CLERKS OF PARCH'S GROVE: This one followed us all the way from Alabama. It's typical of small town badinage and the use of well-known names and idiosyncrasies to drum up local laughter. Its folksong reportage is the forerunner of the modern "Social Notes From All Over" column in the village press.

GIVE MY REGARDS: Few office-holders held the respect accorded to New York City's "Little Flower," Fiorello EL LaGuardia. He was honest and outspoken, even to his own detriment. But this didn't stop the young boys, deprived of their right to deteriorate about the gutter, from poking good- natured fun at the Mayor. Gripes were S.O.P., and this musical diatribe is permeated with the fulsome odor of the Fulton Fish Market and the Gowanus Canal.

THE TENDERFOOT: The satisfying sense of "belonging" to some group is heightened considerably when an "outsider," appropriating from the Mexican and Indian those habits — wrangling habits and riding habits — which they had 50 care fully mastered. When a greenhorn appeared they gave him the business — the roughest horse and the hardest work. Many newcomers wondered why they were called "Tenderfeet" when it wasn't the feet that bore the brunt.

THE MORMON ENGINEER: The story of the Mormons is an epic of courage and faith that can stand beside the histories in the Old Testament. Despite the grim threats which met Joseph Smith's plural marriage pronouncements, the Mormons managed to smile and to sing. Their songs were very often re-written folk tunes. For the saga of Zack, they used "Oh Susanna," the ballad of the Gold Rush.

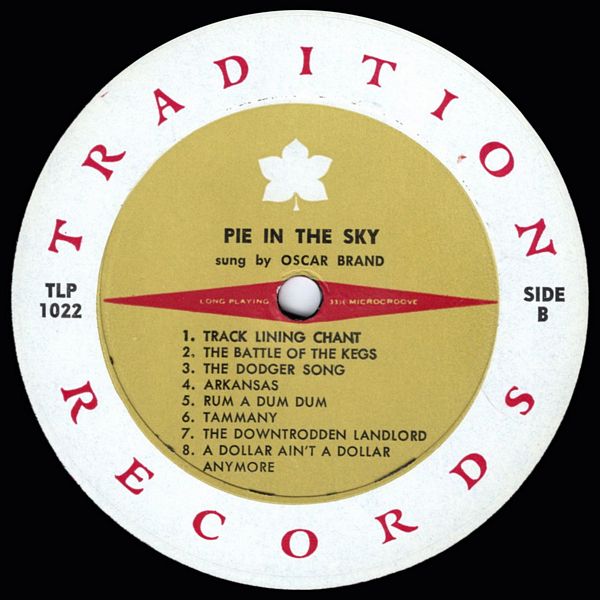

TRACK LINING CHANT: Dave Sear heard this one when he was travelling in the south. It's the kind of work song that keeps the men together and also gives them a chance to let off steam. The sailor, railroad man, or chain gang singer wouldn't have dared to speak the sentiments he could sing with such spirit.

THE BATTLE OF THE KEGS: Under the direction of inventor Bushnell, who had already tried his hand at submarine warfare, the Yankees sent a flotilla of powder-loaded kegs down the Delaware River. Most of the kegs blew up prematurely, but one of them sank a British boat moored on the River. The Red coats became panic-stricken and poured broadside after broad- side into the defenseless waters. Frances Hopkinson. singer o! the Declaration of Independence, signed his name to this song.

THE DODGER SONG: While Bryan was brandishing his Populist pennant and protesting "the cross of gold," the farmer was constructing songs that ridiculed his ancient enemies, the eastern banker, the mortgageman, and the legal eagle. This song got out of hand and ended up by hitting out at all directions. There's a verse anti-everybody in this song, including one against folk-singers, but that one was dropped in deference tothe recording artists.

ARKANSAS: Things were tough enough in Arkansas with out its being the butt of "The Arkansas Traveller" routine, and the outrageous calumny called "Slow Train Through Arkansas." The trains were so slow (it was said I that the farmers complained against passengers leaning out the train windows and milking the cows. And the tight-lipped farmers answered inquiries such as "How did your potatoes turn out?" with "They didn't turn out at all — we had to dig 'em out." "Arkansas" was the word that produced laughter and there was no help for it. Nowadays, the mention of "Brooklyn" has the same effect.

RUM A DUM DUM: For the Mexican War. the populace trotted out every well-known tune in the songbag and fitted them with newly-coined phrases. "Old Dan Tucker" bore lyrics on this song right across the Rio Grande and up to Vera Cruz. Perhaps, the words are less than excruciatingly funny today, but they convulsed the populace in 1847 — which was when the populace needed convulsing.

TAMMANY: Gus Edwards copyrighted this one in 1905 as a vaudeville song. It became a standard on the stage and was immediately parroted and parodied. The braves and sachems of Tammany Hall might have been laughed out of business, but for the fact that they adopted the song and sang it with great amusement. Thus, they were following a precedent set by the minutemen who took the British lampoon, "Yankee Doodle" for their own.

THE DOWNTRODDEN LANDLORD: The clime which produced this song can best be described by recalling the story of the British pastor who warned his flock against whiskey . . ."For it makes you come home drunk ... It makes you shoot at your landlord ... It makes you miss him." Although the song comes from England, it is happily at home here since our land lords, too, come complete with bullseyes.

A DOLLAR AIN'T A DOLLAR ANYMORE: This plaintive air is of modern origin, but has enough older counterparts to make it authentically representative. First sung by Tom Glazer from a sound-truck, it was quickly picked up by pickets, placard-bearers and other curbside protestants. It is as timely as Herb Shriner's remark that he was holding on to his wallet in case money should come back.

— Notes by OSCAR BRAND

About the Singer

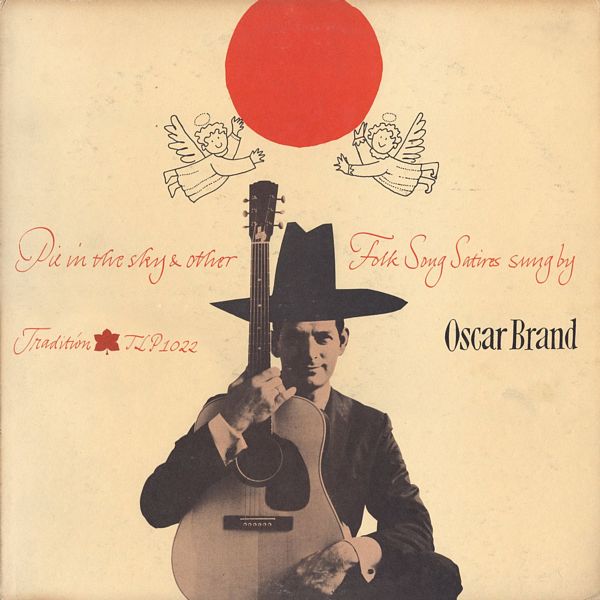

OSCAR BRAND has been singing American songs since his early days in the city of Winnipeg, in the province of Manitoba, in the Dominion of Canada. When his' family moved to the United States, he found, long-settled below the border, and already naturalized, the relatives of the folk-songs he'd known in Canada.

He had no intention of professionally interesting himself in folk music, but there was a tenor banjo in his home — origin unknown — and he learned to play it. He carried it with him during World War II, and discovered it served as a magnet which attracted other folk-singing G.I.s.

When he left the army in 1945, he realized he had so many songs he'd never be able to keep them to himself, so he began broadcasting them publicly over leading radio stations, and, later, over leading television networks. He has used folk music in the making of forty-five motion pictures, has written two books on the subject (which includes Singing Holiday published by Alfred Knopf), numerous articles and reviews, and has sung in every state of the Union. Despite all this, he has managed, every Sunday evening since 1945, to present his "Folksong Festival" on New York City's Municipal Broadcasting System.

This is Mr. Brand's second recording for Tradition. He can also be heard singing American humorous songs on Laughing America, TLP 1014.