|

|

Sleeve Notes

" … I ain't got long, I aint got long

In this murd'er's home … "

— Mississippi Prison Song

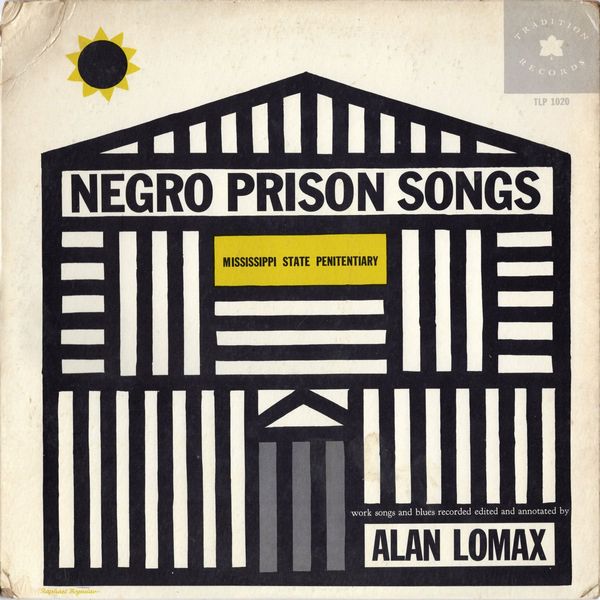

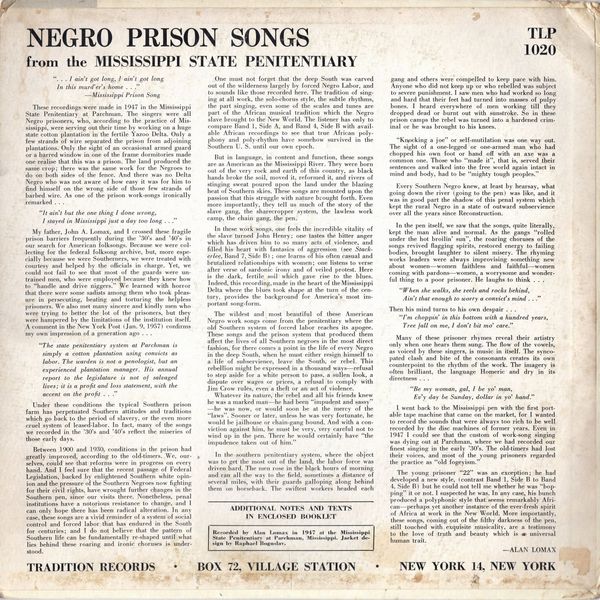

These recordings were made in 1947 in the Mississippi State Penitentiary at Parchman. The singers were all Negro prisoners, who, according to the practice of Mississippi, were serving out their time by working on a huge state cotton plantation in the fertile Yazoo Delta. Only a few strands of wire separated the prison from adjoining plantations. Only the sight of an occasional armed guard or a barred window in one of the frame dormitories made one realise that this was a prison. The land produced the same crop; there was the same work for the Negroes to do on both sides of the fence. And there was no Delta Negro who was not aware of how easy it was for him to find himself on the wrong side of those few strands of barbed wire. As one of the prison work-songs ironically remarked …

"It aint but the one thing I done wrong,

I stayed in Mississippi just a day too long … "

My father, John A. Lomax, and I crossed these fragile prison barriers frequently during the '30's and '40's in our search for American folksongs. Because we were collecting for the federal folksong archive, but, more especially because we were Southerners, we were treated with courtesy and helped by the officials in charge. Yet, we could not fail to see that most of the guards were untrained men, who were employed because they knew how to "handle and drive niggers." We learned with horror that there were some sadists among them who took pleasure in persecuting beating and torturing the helpless prisoners. We also met many sincere and kindly men who were trying to better the lot of the prisoners, but they were hampered by the limitations of the institution itself. A comment in the New York Post (Jan. 9, 1957) confirms my own impression of a generation ago …

"The state penitentiary system at Parchman is simply a cotton plantation using convicts as labor. The warden is not a penologist, but an experienced plantation manager. His annual report to the legislature is not of salvaged lives; it is a profit and loss statement, with the accent on the profit … "

Under these conditions the typical Southern prison farm has perpetuated Southern attitudes and traditions which go back to the period of slavery, or the even more cruel system of leased-labor. In fact, many of the songs we recorded in the '30's and '40' s reflect the miseries of those early days.

Between 1900 and 1930. conditions in the prison had greatly improved, according to the old-timers. We. ourselves, could see that reforms were in progress on every hand. And I feel sure that the recent passage of Federal Legislation, backed by enlightened Southern white opinion and the pressure of the Southern Negroes now fighting for their civil rights, have wrought further changes in the Southern pen. since our visits there. Nonetheless, penal institutions have a notorious resistance to change, and I can. only hope there has been radical alteration. In any case, these songs are a vivid reminder of a system of social control and forced labor that has endured in the South flor centuries: and I do not believe that the pattern of life can be fundamentally re-shaped until what these roaring and ironic choruses is understood.

One must not forget that the deep South was carved out of the wilderness largely by forced Negro Labor, and to sounds like those recorded here. The tradition of singing at all work, the solo-chorus style, the subtle rhythms, the part singing, even some of the scales and tunes are part of the African musical tradition which the Negro slave brought to the New World. The listener has only to compare Band 1, Side A, and Band 4, Side B with available African recordings to see that true African polyphony and poly-rhythm have somehow survived in the Southern U. S. until our own epoch.

But in language, in content and function, these songs are as American as the Mississippi River. They were born out of the very rock and earth of this country, as black hands broke the soil, moved it, reformed it, and rivers of stinging sweat poured upon the land under the blazing heat of Southern skies. These songs are mounted upon the passion that this struggle with nature brought forth. Even more importantly, they tell us much of the story of the slave gang, the sharecropper system, the lawless work camp, the chain gang, the pen.

In these work songs, one feels the incredible vitality of the slave turned John Henry; one tastes the bitter anger which has driven him to so many acts of violence, and filled his heart with fantasies of aggression (see Stackerlee. Band 7, Side B) ; one learns of his often casual and brutalized relationships with women; one listens to verse after verse of sardonic irony and of veiled protest. Here is the dark, fertile soil which gave rise to the blues. Indeed, this recording, made in the heart of the Mississippi Delta where the blues took shape at the turn of the century, provides the background for America's most important song-form.

The wildest and most beautiful of these American Negro work songs come from the penitentiary where the old Southern system of forced labor reaches its apogee. These songs and the prison system that produced them affect the lives of all Southern negroes in the most direct fashion, for there comes a point in the life of every Negro in the deep South, when he must either resign himself to a life of subservience, leave the South, or rebel. This rebellion might be expressed in a thousand ways — refusal to step aside for a white person to pass, a sullen look, a dispute over wages or prices, a refusal to comply with Jim Crow rules, even a theft or an act of violence.

Whatever its nature, the rebel and all his friends knew he was a marked man — he had been "impudent and sassy" — he was now, or would soon be at the mercy of the "laws". Sooner or later, unless he was very fortunate, he would be jailhouse or chain-gang bound. And with a conviction against him, he must be very, very careful not to wind up in the pen. There he would certainly have "the impudence taken out of him."

In the southern penitentiary system, where the object was to get the most out of the land, the labor force was driven hard. The men rose in the black hours of morning and ran all the way to the field, sometimes a distance of several miles, with their guards galloping along behind them on horseback. The swiftest workers headed each gang and others were compelled to keep pace with him. Anyone who did not keep up or who rebelled was subject to severe punishment. I saw men who haoT worked so long and hard that their feet had turned into masses of pulpy bones. I heard everywhere of men working till they dropped dead or burnt out with sunstroke. So in these prison camps the rebel was turned into a hardened criminal or he was brought to his knees.

"Knocking a joe" or self-mutilation was one way out. The sight of a one-legged or one-armed man who had chopped his own foot or hand off with an axe was a common one. Those who "made it", that is, served their sentences and walked into the free world again intact in mind and body, had to be "mighty tough peoples."

Every Southern Negro knew, at least by hearsay, what going down the river (going to the pen) was like, and it was in good part the shadow of this penal system which kept the rural Negro in a state of outward subservience over all the years since Reconstruction.

In the pen itself, we saw that the songs, quite literally, kept the man alive and normal. As the gangs "rolled under the hot broilin' sun", the roaring choruses of the songs revived flagging spirits, restored energy to failing bodies, brought laughter to silent misery. The rhyming works leaders were always improvising something new about women — women faithless and faithful — women coming with pardons — women, a worrysome and wonderful thing to a poor prisoner. He laughs to think …

"When she walks, she feels and rocks behind,

Ain't that enough to worry a convict's mind … "

Then his mind turns to his own despair

I'm choppin in this bottom with a hundred years,

Tree fall on me, I don't bit mo' care."

Many of these prisoner rhymes reveal their artistry only when one hears them sung. The flow of the vowels, as voiced by these singers, is music in itself. The syncopated clash and bite of the consonants creates its own counterpoint to the rhythm of the work. The imagery is often brilliant, the language Homeric ariH dry in its directness …

"Be my woman, gal, I be yo' man,

Ev'y day be Sunday, dollar in yo' hand."

I went back to the Mississippi pen with the first portable tape machine that came on the market, for I wanted to record the sounds that were always too rich to be well recorded by the disc machines of former years. Even in 1947 I could see that the custom of work-song singing was dying out at Parchman, where we had recorded our finest singing in the early '30's. The old-timers had lost their voices, and most of the young prisoners regarded the practice as "old fogeyism."

The young prisoner "22" was an exception; he had developed a new style, (contrast Band 1, Side B to Band 4, Side B) but he could not tell me whether he was "bopping" it or not. I suspected he was. In any case, his bunch produced a polyphonic style that seems remarkably African — perhaps yet another instance of the ever-fresh spirit of Africa at work in the New World. More importantly. these songs, coming out of the filthy darkness of the pen, still touched with exquisite musicality, are a testimony to the love of truth and beauty which is a universal human trait.

— ALAN LOMAX