|

|

Sleeve Notes

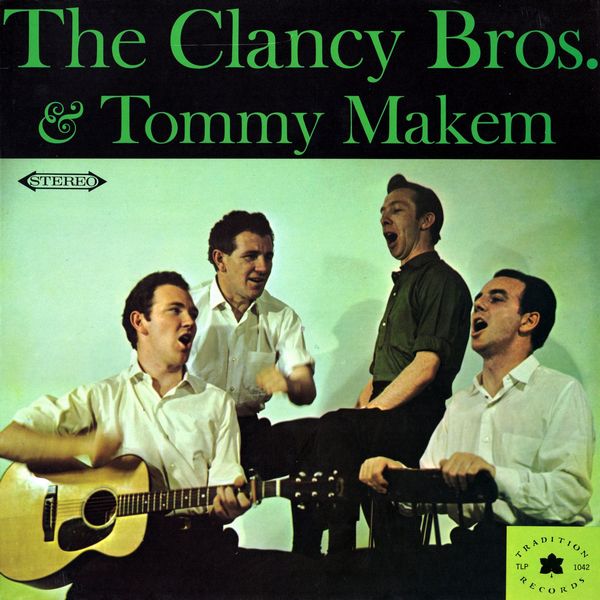

There's always been something to sing about when folk musicians and their admirers get together. But in the spring of 1961, as the upward spiral of the folk-music revival in America went higher and higher, the success of one group caused a particularly joyous outburst of song.

The group we're talking about, it won't surprise you to learn, is none other than the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem. And the reason for all the gaiety is that America has taken to its heart these four, tough-fisted, gentle-hearted Irish singers. This is a not altogether unexpected phenomenon. For one thing, it has opened up the flood-gates of an entirely new freshet of song for American listeners. And out pours the rushing, clean waters of Irish folk music, with its lilting charm, fierce independence of spirit, melodic inventiveness and whimsical view of life.

Still another reason for being happy about the success of Messrs. Clancy and Makem is that for the first time in this revival the line between "authentic" and "entertainment" has been narrowed.

How often in the past has the American listening audience had to endure only prettied-up and popularized arrangements of folk melodies? Yes, there was always a core of devotees who knew the real article, who said that the real folk music was so much richer, deeper and more durable than anything the popularizers were offering.

What changed? More than anything, it was the taste of the audience that began to change. City people got a sniff of folk music and gradually got curious to know what the unadorned, straight product was like. Somehow the ballads of Jean Ritchie or the craggy voices of southern mountaineers were being taken on their own terms, and appreciated for what they were. The audience began to understand that folk music can sometimes be a bit rough around the edges and not always the most technically polished, yet the conviction and belief and artistry would still be there.

This has been brought about by many performers who have refused to change their standards. Like a bunch of stalwart rocks in an eddying stream, these singers held on firmly to their styles and their ideals of performing. And the Clancys and Tommy Makem, traditional singers all, are turning out to be among the biggest, boldest rocks in the stream.

Now the group is finally getting the acclaim it justly deserves. They've sung at Carnegie Hall and Town Hall. They've appeared on Ed Sullivan's television show and Arthur Godfrey's radio show. They have recorded for Columbia Records (but will also continue to be heard on their "home" company, Tradition Records). They have appeared twice at Gerde's Folk City, One Sheridan Square, the Blue Angel, the Gate of Horn in Chicago and have also appeared at the Village Gate in Manhattan, the hungry i in San Francisco, the Playboy Club in Chicago, and in Minneapolis with the comic Bob Newhart.

One Greenwich Village "folknik" became worried when she heard that the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem had gone to New York's swank, sophisticated Blue Angel. "Oh, they've gone and sold out," she fretted, unknowingly. "Nonsense," replied a friend and admirer who knew what they were doing at the Blue Angel. "They haven't changed a bit," he said, "the audience has changed."

It's a long way from home from the Clancy residence, a limestone and mortar, slate-roofed house in Carrick-on-Suir, Tipperary , to the Blue Angel. And it's an equal distance from Tommy Makem's home in Keady, County Armagh, to the plush room, as he described the place on first seeing it. "with mattresses on the wall."

But the quartet, ramblers, adventurers and actors all, have not changed what they do. There's still the ring of honesty about their songs, there's still the spirit of good fun and infectious happiness that irradiates their work. Tradition is the backbone of folk music and it is often the backbone of strong men in a world where the quick profit and the easy way out have become almost symptomatic institutions.

Pat Clancy is the oldest of the clan, and is president of Tradition records. He has acted for nearly ten years and sung for more than thirty. He served in the Irish Republican Army and volunteered for the Royal Air Force in World War II. His brother, Tom, is next in age, and is a successful actor on Broadway and television. He has been a cook, a welder and a warrant officer in the R.A.F. Liam has appeared at the Poet's Theatre in Cambridge, Mass., on various television dramatic shows, and done folk-song collecting in the highlands of Scotland and the Southeastern United States. Tommy Makem is the most recent emigré from Ireland, but has been making up for "lost" time with a rigorous schedule of acting and singing, with Pete Seeger and the Clancy's.

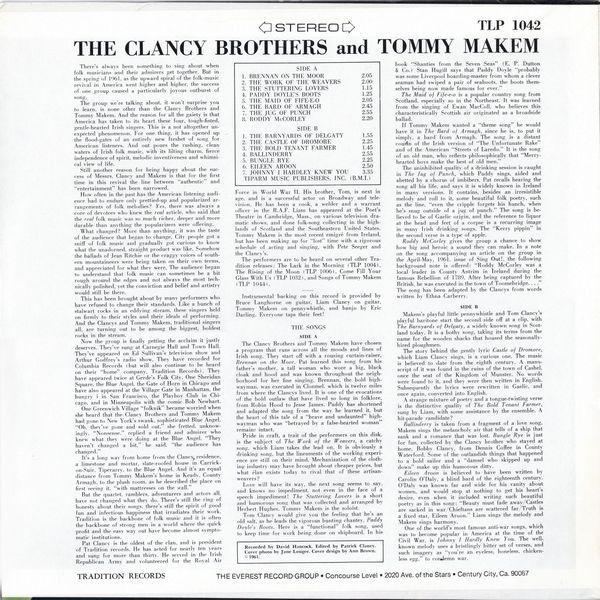

The performers are to be heard on several other Tradition releases: The Lark in the Morning (TLP 1004), The Rising of the Moon (TLP 1006), Come Fill Your With Us (TLP 1032), and Songs of Tommy Makem (TLP 1044).

Instrumental backing on this record is provided by Bruce Langhorne on guitar Liam Clancy on guitar, Tommy Makem on penny whistle, and banjo by Eric Darling. Everyone taps their feet!

THE SONGS

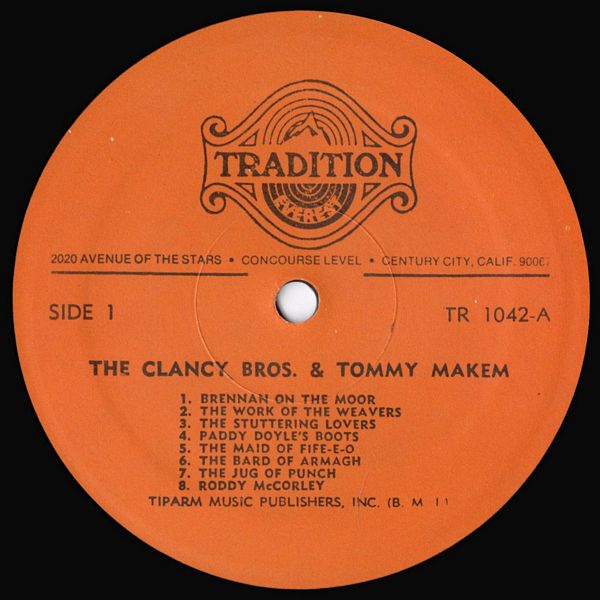

SIDE A

The Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem have chosen a program that runs across all the moods and lines of Irish song. They start off with a rousing curtain-raiser,

Brennan on the Moor. Pat learned this song from his father's mother, a tall woman who wore a big, black cloak and hood and was known throughout the neighborhood for her fine singing. Brennan, the bold highwayman, was executed in Clonmel, which is twelve miles from where the Clancys lived. It is one of the evocations of the bold outlaw that have lived so long in folklore, from Robin Hood to Jesse James. Paddy has shortened and adapted the song from the way he learned it, but the heart of this tale of a "brave and undaunted" highwayman who was "betrayed by a false-hearted woman" remains intact.

Pride in craft, a trait of the performers on this disk, is the subject of The Work of the Weavers, a catchy song, which Liam takes the lead on. It is obviously a drinking song, but the lineaments of the working experience are still on their mind. Mechanization of the clothing industry may have brought about cheaper prices, but what elan exists today to rival that of these artisan-weavers?

Love will have its way, the next song seems to say, and knows no impediment, not even in the face of a speech impediment! The Stuttering Lovers is a short and humorous song that was collected and arranged by Herbert Hughes. Tommy Makem is the soloist.

Tom Clancy would give you the feeling that he's an old salt, as he leads the vigorous bunting chantey, Paddy Doyle's Boots. Here is a "functional" folk song, used to keep time for work being done on shipboard. In his book "Shanties from the Seven Seas" (E. P. Dutton & Co.) Stan Hugill says that Paddy Doyle "probably was some Liverpool boarding-master from whom a clever seaman had swiped a pair of seaboots. the boots themselves being now made famous for ever."

The Maid of Fife-e-o is a popular country song from Scotland, especially so in the Northeast. It was learned from the singing of Ewan MacColl, who believes this characteristically Scottish air originated as a broadside ballad.

If Tommy Makem wanted a "theme song" he would have it in The Bard of Armagh, since he is, to put it simply, a bard from Armagh. The song is a distant cousin of the Irish version of "The Unfortunate Rake" and of the American "Streets of Laredo." It is the song of an old man, who reflects philosophically that "Merry-hearted boys make the best of old men."

The uninhibited quality of a drinking session is caught in The Jug of Punch, which Paddy sings, aided and abetted by a chorus of imbibers. Pat recalls hearing the song all his life, and says it is widely known in Ireland in many versions. It contains, besides an irresistible melody and roll to it, some beautiful folk poetry, such as the line, "even the cripple forgets his hunch, when he's snug outside of a jug of punch." The song is believed to be of Gaelic origin, and the reference to liquor at the head and feet of a corpse is a recurring image in many Irish drinking songs. The "Kerry pippin" in the second verse is a type of apple.

Roddy McCorley gives the group a chance to show how big and heroic a sound they can make. In a note on the song accompanying an article on the group in the April-May, 1961, issue of. Sing Out!, the following background note is offered: "Roddy McCorley was a local leader in County Antrim in Ireland during the famous Rebellion of 1789. After being captured by the British, he was executed in the town of Toomebridge …" The song has been adapted by the Clancys from words written by Ethna Carberry.

SIDE B

Makem's playful little penny whistle and Tom Clancy's playful baritone start the second side off at a clip, with The Barnyards of Delgaty, a widely known song in Scotland today. It is a bothy song, taking its terms from the name for the wooden shacks that housed the seasonally-hired ploughmen.

The story behind the gently lyric Castle of Dromore, which Liam Clancy sings, is a curious one. The music is believed to date from the eighth century. A manuscript of it was found in the ruins of the town of Cashel, once the seat of the Kingdom of Munster. No words were found to it, and they were then written in English. Subsequently the lyrics were rewritten in Gaelic, and once again, converted into English.

A strange mixture of poetry and a tongue-twisting verse is the distinctive quality of The Bold Tenant Farmer, sung by Liam, with some assistance by the ensemble. A hit-parade candidate?

Ballinderry is taken from a fragment of a love song. Makem sings the melancholy air that tells of a ship that sank and a romance that was lost. Bungle Rye is just for fun, collected by the Clancy brother who stayed at home, Bobby Clancy, from Dennis Coffee in County Waterford. Some of the outlandish things that happened to a bold sailor and a "damsel who skipped up and down" make up this humorous ditty.

Eileen Aroon is believed to have been written by Carolin O'Daly, a blind bard of the eighteenth century. O'Daly was known far and wide for his vanity about women, and would stop at nothing to get his heart's desire, even when it included writing such beautiful poetry as in this song: "Beauty must fade away/Castles are sacked in war/Chieftains are scattered far/Truth is a fixed star, Eileen Aroon." Liam sings the melody and Makem sings harmony.

One of the world's most famous anti-war songs, which was to become popular in America at the time of the Civil War. is Johnny I Hardly Knew You. The well-known melody uses a bristlingly bitter set of verses, and such imagery as "you're an eyeless, boneless, chicken-less egg," to condemn war.